In Washington, D.C., Frederick Douglass’ Cedar Hill honors a life passionately devoted to freedom

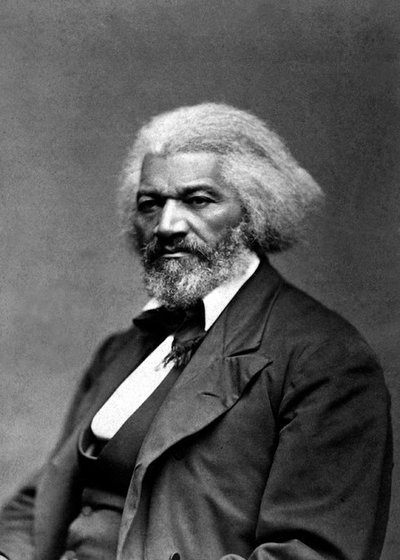

His mother named him Frederick Augustus Bailey. He’d choose the name Douglass later, and under that name, he’d lead a life of astonishing fortitude and valor: escaped slave; brilliant, self-taught orator and writer; and titan of the abolitionist movement. Though his true birthday is unknown, he was said to have celebrated it on Feb. 14.

A gracious 19th-century home in Washington, D.C., named Cedar Hill reveals Douglass’ life in all its adventure and achievement. It also lets visitors see the private man: husband, father, grandfather, lover of books, travel and music.

A Powerful Voice for the Anti-Slave Movement

In New Bedford, Douglass chose his new surname, borrowing it from the Scottish lord in Sir Walter Scott’s novel The Lady of the Lake, but adding a second S on the end. Here he began his public career. He began to speak at American Anti-Slavery Society meetings, so compellingly that he was paid to travel around New England — and later in New York state, Ohio and Indiana — telling his own story of slavery and escape. The work had its dangers — in Indiana, a mob beat him and broke his right hand. But he became a national figure, especially after he published his autobiography in 1845.

In the years leading up to the Civil War, Douglass was one of the most powerful voices of the anti-slavery movement, drawing large crowds in the United States and in England, Scotland and Ireland. He founded an anti-slavery newspaper, The North Star. During the Civil War, he pushed President Abraham Lincoln to understand the necessity of emancipating the South’s slaves; he also helped recruit black soldiers for the famed 54th Regiment in the Massachusetts infantry.

After the war, he would become president of the National Convention of Colored Citizens and, thanks to his friendship with Susan B. Anthony, a strong advocate for women’s rights. By the time he moved into Cedar Hill, he was among the most famous figures in the U.S.

Over the next few years, Douglass acquired surrounding land, expanding his property to 14 acres. He also expanded the living quarters, building a two-story addition on the rear of the house, and turning the original kitchen into a dining room, then adding a new kitchen. The impressive library was completed about 1886. By Douglass’ death, Cedar Hill was a 21-room mansion.

After Douglass’ death in 1895, his second wife, Helen Pitts Douglass, lobbied the federal government to designate Cedar Hill a historic landmark. It was managed by the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association until 1962, when it became part of the National Park Service.

Cedar Hill underwent a $2.7 million renovation from 2004 to 2007. Among the most noticeable changes was the home’s exterior color. It went from white to the dark beige you see now — the shade chosen to match the color of the home in his last years.

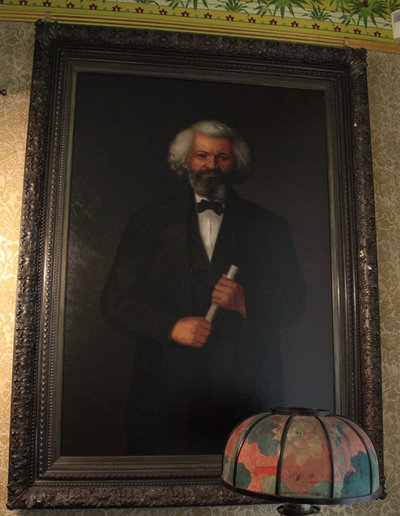

Cedar Hill has two parlors — the informal West Parlor, reserved for family and friends, and the more formal East Parlor. By the time Douglass moved into Cedar Hill, he was a nationally known figure who numbered many of the nation’s most prominent politicians, journalists and social activists among his acquaintances. These visitors would be ushered into the East Parlor after first presenting their calling cards to Cedar Hill’s doorman.

The Sarah J. Eddy portrait shown here hangs in the home’s East Parlor and shows Douglass during the time he lived here.

Cedar Hill was a busy place. Along with his important guests, Douglass also frequently hosted the 21 grandchildren of his five children (two daughters, three sons). Much of this family fun took place in the West Parlor, also known as the sitting room.

Douglass, an accomplished violinist, passed on his musical gifts to his children and grandchildren.

The violin on display in the West Parlor was owned by his grandson Joseph Douglass, who became a noted classical performer.

While the clock itself was made in Switzerland, the carving it rests in was done by Eddy, who also painted the portrait of Douglass that hangs in the East Parlor.

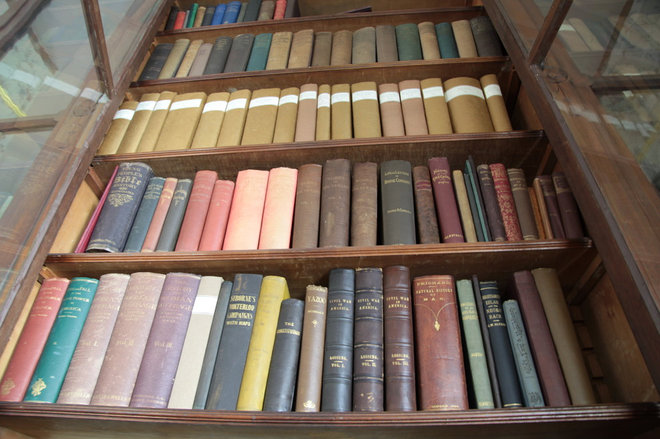

If the West Parlor was the heart of Cedar Hill, the library was its soul. As a child, Douglass had to battle to learn to read and write; as a man, his gifts as public speaker, journalist and memoirist would earn him political power, a respectable living and, in the end, literary immortality.

The library today is much as Douglass left it. The shelves are filled with nearly 1,000 books on history, science, government, law, religion and literature. His chair dates from 1857 and was originally used in the House of Representatives; Douglass bought it from a furniture dealer in the 1870s.

Walls are decorated with portraits of people Douglas admired — among them, Joseph Cinque, who led the famed 1839 revolt on Spanish slave ship La Amistad, and friend and women’s rights advocate Anthony.

When Douglass expanded Cedar Hill, he moved the kitchen inside the house — unusual for the 1870s, when most kitchens were built separately to keep kitchen fires from spreading to the main structure. The innovation meant that Douglass initially had trouble buying fire insurance for his new home. While not original, the coal stove is similar to the one that would have been used by the Douglass family. Anna was a good cook, famous within her family for her biscuits.

Douglass’ bedroom contains his Renaissance Revival bed, along with personal items including a set of dumbbells he used as part of his daily exercise routine; he also took regular walks around his property.

On Feb. 20, 1895, Douglass returned to Cedar Hill after delivering a speech, suffered a massive heart attack and died. After his death, Helen worked to have Cedar Hill preserved as a historic landmark.

Visiting Cedar Hill

Frederick Douglass National Historic Site is located at 1411 W St. S.E. in Washington, D.C. The house can be seen only on 30-minute guided tours. Tour reservations are recommended and can be made at recreation.gov or by calling (877) 444-6777.

Thorough and captivating post about Douglass. I knew about (and have read) his writings, but not about his history after becoming a famous statesman. This man was an incredible human being. I didn’t know about his house or the tour, and will make sure to go there soon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on kelvintysblog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the reblog

LikeLike